Marketing

Dimensions of the Revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory - Datiranje za seks

Login using

Click here: Dimensions of the Revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory

Moreover, a review by our own group showed that similar personality constructs, such as Neuroticism or Harm Avoidance , have also been linked to the hippocampus, but in the opposite direction—that is, a negative association between negative emotionality and gray matter volume in structures of the temporal lobe is also plausible. The RSQ showed a positive correlation with the SOPA-R and PBPI, and this correlation was significant; this shows the RSQ can be predictive for pain attitudes and pain beliefs and perception. The effect of behavioral inhibition and approach on normal social functioning. Conclusion: Overall, the findings indicated that the RSQ has good psychometric properties in chronic pain samples, and the tool can be used in studies of chronic pain.

Strength of motivation and efficiency of performance. His theory emphasized the relationship between personality and sensitivity to reinforcement i. There is controversy over the precise cut-off scores of fit indices.

Psychometric properties revised reinforcement sensitivity theory (r-RST) scale in chronic pain patients - Motivation and Emotion, 16, 143- 155. The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system 2nd ed.

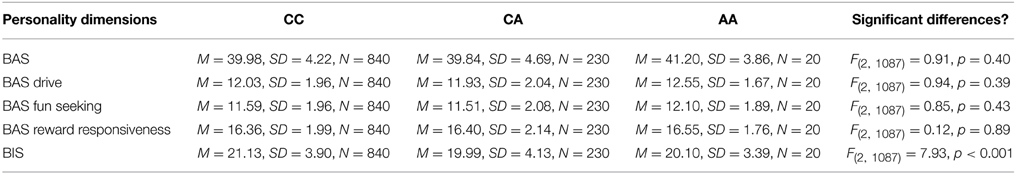

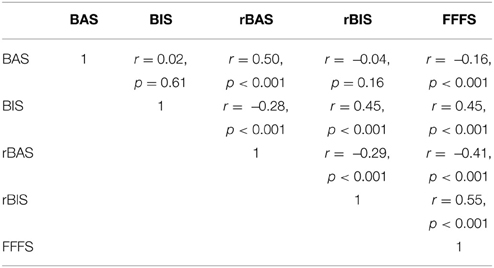

Finally, this same subgroup of participants provided buccal swaps for the investigation of the arginine vasopressin receptor 1a AVPR1a gene. Here, a functional genetic polymorphism rs11174811 on the AVPR1a gene was shown to be associated with individual differences in both the revised BIS and classic BIS dimensions. Introduction The Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory RST of personality has in recent years become one of the most prominent biologically oriented theories in personality psychology ;. At the core of the classic form of this theory are the behavioral activation and behavioral inhibition systems BAS and BIS, respectively. Individual differences in the functioning of the BIS and BAS are thought to provide the biological foundation for complex personality traits see also. Gray proposed that the BAS is anchored in mesolimbic dopaminergic pathways e. Here, mesolimbic dopamine function is thought to underpin energized approach behavior toward appetitive stimuli. Individuals with stronger dopaminergic firing in these brain regions might be characterized as full of energy, having a tendency toward outgoing explorative behavior, and being more motivated to pursue rewards e. In contrast, individuals with a more reactive BIS might be characterized as more anxious, avoidant, and more motivated to avoid threat or punishment. According to the original conceptualization of RST, the BIS is hypothesized to be anchored around a core network comprising the septo-hippocampal-system e. A major revision to RST has resulted in a somewhat updated understanding of the systems described above ; , with particularly notable implications for the role of the BIS and what has now been termed the Fight Flight Freezing system FFFS, reflecting Fear. In the classic version of the RST, the BAS and BIS were thought to be activated only by conditioned rewarding and punishing stimuli, respectively. In the revised RST, the BAS is proposed to be responsive to all rewarding and appetitive stimuli, while the FFFS is proposed to be responsive to all punishing and threatening stimuli. Conversely, the BIS is now thought to be activated by instances of goal conflict, such as when a threatening stimulus must be approached, or when mixed signals of reward and punishment are present. In rodent models, such conflict is well represented by a rodent being placed in an experimental setting prepared with cat odor. While the visual information clearly indicates that no cat is in close proximity, the olfactory senses of the rodent suggest otherwise. Such experiments have been conducted in a setting called the visible burrow system by and , , among others. Observable behavior accompanying BIS activation is thought to include careful and slow approach behavior toward the potentially dangerous stimuli, and risk assessment behaviors e. This careful approach behavior in a potentially dangerous situation is important, because it can generate new information to help solve the conflict is a cat near, or not? As outlined above, both the hippocampus and the amygdala have been outlined as playing an important role for the BIS ; pp. This idea has already received support from studies in the human neuroscience literature. For example, a study by observed a positive correlation between gray matter volumes of the hippocampus and amygdala, and scores on a questionnaire measuring BIS reactivity. Supporting these findings, were also able to observe a positive correlation between BIS scores and hippocampus volume. Of note, these studies administered self-report inventories which were originally developed to measure the classic BIS and BAS dimensions. Moreover, a review by our own group showed that similar personality constructs, such as Neuroticism or Harm Avoidance , have also been linked to the hippocampus, but in the opposite direction—that is, a negative association between negative emotionality and gray matter volume in structures of the temporal lobe is also plausible. One of the most pressing issues in personality psychology when dealing with the revised RST is the measurement of individual differences in the BIS reflecting anxiety and the FFFS reflecting fear in terms of the changes made to the theory. There already exists a first questionnaire, the Reinforcement Sensitivity Questionnaire RSQ , measuring the revised RST, but the items were only published in a Serbian book chapter and not in English language. However, the authors have published an article on validation data of their RSQ where the principles of the questionnaire construction are described. In the RSQ the BAS is conceptualized with a focus on behaviors indicating sensitivity to signals of reward rather than on those indicating sensitivity to reward. The FFFS is represented by three distinct scales: Fight items include aggressive reactions to the emotion of fear caused by present threats, Freeze items express the inability to articulate necessary verbal responses to threat and Flight is defined as reaction to real danger which can be avoided. It is important to mention that the questionnaire construction and data collection of the RSQ and the Reuter and Montag rRST-Q happened parallel in time so that we had no chance to profit from the ideas and results of Smederevac et al. Theoretical overlap and difference between the RSQ and our rRST-Q are described in the Discussion section. On this basis, the first aim of the present study is to provide a new measurement tool for the revised RST, with a particular focus on disentangling measurement of the BIS and FFFS constructs. In this initial investigation, we employ molecular genetic methods to investigate the validity of our new measure. Of particular importance to the present study is that the emotion of anxiety is influenced by a large number of neurotransmitters, including gamma amino butyric acid GABA; e. The nonapeptide oxytocin has become a major research focus as it seems to play an important role in social cognition and has been associated with trust behavior. Similar effects have been observed by , who reported a down-regulation of the amygdala while processing emotional faces after administration of oxytocin. As noted above, found that meeting a trusted person could trigger oxytocin secretion, which results in the dampening of alarm signals usually elicited by the amygdala when encountering a stranger. Therefore, oxytocin could be of particular relevance for understanding the emotion of social anxiety, elicited by uncertainty when meeting and engaging with strangers. There has been even less social neuroscience research on the role of the nonapeptide vasopressin in the context of social anxiety. The initial studies in this area with humans point toward an equally important role for vasopressin in social cognition. Of particular importance is the study by , reporting that the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex was more strongly activated under the influence of vasopressin, compared to placebo, when humans participated in a classic face matching paradigm using fearful and angry faces. During fear processing strong subcortical signals can be observed, putatively due to a lack of inhibition by the prefrontal cortex. Among others, observed that the administration of AVP in septal regions attenuates anxiety-related behavior in the form of longer time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze test in rats. The major target of AVP for cell signaling is the arginine vasopressin receptor 1 a AVPR1a. Consequently, knocking out the gene coding for AVPR1a could be associated with a reduction in anxiety, as measured by the elevated plus maze test mentioned above. In order to translate these interesting findings to humans, molecular genetic association studies have already investigated genetic variants on the AVPR1A and AVPR1B genes in relation to individual differences in a vast range of human behaviors, including anxiety related personality traits ; , altruistic behavior , musical aptitude , pair bonding , and autism ;. In the present study, we hypothesized that genetic variation on the AVPR1a gene would be related to individual differences in measures of BIS both the classic and revised form , but should not be associated with our measure of FFFS. Expression levels in samples homozygous for the major C-allele genotype CC were significantly lower than in samples with at least one minor A-allele genotypes AA or CA;. In sum, the main aims of the present research are as follows: First, we report on the development of a new questionnaire measuring individual differences in the revised constructs of Gray and McNaughton's BAS, BIS and FFFS dimensions. We would expect only moderate correlations between the same constructs measured across the two self-report-inventories given the differences between the classic and revised models of RST, as outlined above. We would also expect only low to moderate correlations between the revised FFFS measure in the rRST-Q and the BIS scale from the Carver and White scale, on the same basis. The third aim of the study was to examine whether a genetic variant is associated with individual differences in the BIS. As AVP has been understudied in the context of anxiety although the first evidence points toward such an association, as outlined above so far, we tested for a link between rs11174811 and the BIS, as measured by both the Reuter and Montag and the Carver and White scale. Given the small number of studies dealing with the functional polymorphism on the AVPR1a gene in the context of negative emotionality, we have not provided a directional hypothesis for this potential effect. Methods Participants The results of this study will be presented across three sections. The participants were predominantly university students in both the German and English samples. The study was approved by the psychology ethics committee of the University of Bonn, Germany. Measures Two questionnaires were administered to measure individual differences in RST-relevant personality constructs. We administered a new questionnaire called Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q to measure individual differences in the revised BAS, BIS, and FFFS constructs. The original item pool for the rRST-Q consisted of 34 items; three items were excluded during the development process to improve both the factor structure and the internal consistencies of the scale. The German version of the scale was translated into English by a bilingual German-English speaker; the translated items were then checked by a native English speaker and some minor modifications were made to several of the items. This version was then back-translated to German by a different bilingual German-English speaker, and the resultant back-translated German items were checked against the original German items for consistency. Tables , present all items from Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q in German and English. The BAS dimension in this scale has item content measuring approach and goal-directed behavior; those who score high on this BAS scale could be described as bold, adventurous and may show stronger energy and drive when approaching appetitive stimuli. Revised BIS Higher BIS activity should reflect responses to goal conflict and situations of uncertainty, including hesitation, risk assessment or wary behavior. As proposed by , three kinds of conflict are possible in principle i. Individuals with a more reactive BIS will tend to have difficulty making decisions when two equally attractive or unattractive options are presented and one option needs to be chosen e. Revised FFFS In revised RST, the FFFS is associated with three kind of defensive or avoidant responses, namely Fight, Flight, and Freezing. Accordingly, in the rRST-Q, high overall trait FFFS is characterized by low fight, high flight and high freezing behavior. This may appear at odds with the notion of defensive attack e. However, in the revised RST fight behavior is only observable if the distance between predator and prey is close to zero, leaving no option for flight or freezing. The probability of such situations occurring for human beings is extremely low. Furthermore, particularly fearful individuals are perhaps least likely to find themselves in a situation in which there is zero distance between them and a source of threat. As a consequence, and in line with the notion that activity of the FFFS is associated with withdrawal behavior in broad terms, we would characterize a high trait FFFS individual as high in flight and freezing behavior, but a low scorer on fight behavior. A person who is not willing to fight when being attacked might typically withdraw more quickly from unpleasant situations, compared to a person who is more willing to fight when threatened. Clearly when filling in a questionnaire such as this, asking a person to reflect on his or her behavior can only represent an indirect approach to understanding subcortical brain activity in the brain systems of the revised RST. In addition, operationalizing the FFFS as described here putatively leads to positive inter-correlations between all three FFFS subscales. The BIS scale consists of seven items and the BAS scales comprise thirteen items. The BAS scale can be split in to three subscales: BAS drive four items , BAS fun seeking four items and BAS reward responsiveness five items. Four filler items are presented to participants, but not analyzed. The internal consistencies for the scales derived from the present data set and contrasted with the data presented by are presented in the Results section see Table. Genetic Analyses DNA was extracted from buccal cells. Automated purification of genomic DNA was conducted by means of the MagNA Pure ® LC system using a commercial extraction kit MagNA Pure LC DNA isolation kit; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany. Results The Results section of the study is split into three sections. The first section presents descriptive data as well as psychometric data reliabilities for both a German and an English version of Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q. In addition, confirmatory factor analyses CFAs are presented that test the revised RST model e. The third section of the results reports a genetic validation of the new RST questionnaire, with a specific focus on the potential relation between BIS sensitivity and the AVPR1a gene. Section 1: Psychometric Analysis of Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q In Table , means and standard deviations for the German version of Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q are provided, including descriptive statistics for the male and female participants separately. In order to test if the factor structure of the Revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory Questionnaire rRST-Q is in accordance with our theoretical assumptions, we ran CFAs using the LISREL software package LISREL 8. Given the ordinal nature of the questionnaire data a 4-point Likert scale , the CFAs were based on polychoric covariance matrices and asymptotic covariance matrices. Parameter estimates were calculated using the Robust Diagonally Weighted Least Squares DWLS method. Of note, the shared variance between the classic BAS from the Carver and White scale and the revised BAS from the new inventory is about 25%. Similarly, the shared variance between the classic BIS scale and its revised form was also around 25%. Section 3: Analysis of the Genetic Variation of the AVPR1a Gene in Relation to the Behavioral Inhibition System In this third section of the results, we explored the relation of the AVPR1a gene and its functional polymorphism rs11174811 with both the classic and revised BIS scales. No gender by gene interaction effects could be observed on the BIS scales. The inclusion of age as a covariate did not change the significant influence of rs11174811 on the BIS. A post-hoc test revealed that the contrast for the genotypes CC vs. As shown in Tables , , no significant effect of rs11174811 could be detected on our measure of FFFS, nor on any of the other RST dimensions across both personality inventories. Discussion This study had three key aims. First, we sought to develop a new self-report measure for the revised RST in order to better distinguish between aspects of personality concerned with fear and anxiety. Given the putative separation of the FFFS and the BIS in the revised RST in terms of behavioral functioning and their neuropsychopharmacological bases, self-report measures that seek to separate the FFFS and BIS are desirable. On that basis, and in line with revised RST, the new inventory attempts to disentangle the emotions of fear and anxiety by including separate scales for the revised BIS reflecting anxiety and for the FFFS reflecting the emotion of fear. Of note, we designed the BIS scale to measure hesitation and cautious behavior in conflict situations, such as deciding between two even potentially positive options e. As well as difficulties in behavioral choice, cognitions related to tolerance of uncertainty are also reflected in the revised BIS in our questionnaire e. The scale for the FFFS, measuring individual differences in fear tendencies, comprises the most important classes of behavioral fear responses, namely Fight, Flight, and Freezing. Finally, the BAS scale is designed to measure individual differences in reward-seeking, drive and energy e. Despite some similarities in the conceptualization of the revised RST between the RSQ by and Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q there are also apparent differences. With respect to the BIS, the rRST-Q concentrates on conflicts without focusing on irrational interpretations of stimuli as the RSQ does. The conceptualization of the BAS is broader in the rRST-Q than in the RSQ: besides sensitivity to signals of reward, drive, energy and risk taking are also included. The correlations between the dimensions within Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q show that the BAS is negatively associated with both the BIS and FFFS. In line with this, both the BIS and the FFFS are positively correlated and can be positioned on the side of negative emotionality. Importantly, from a psychometric point of view, our new inventory shows good internal consistencies across the scales and good model fit when using CFA to model the latent variables of the questionnaire. It should be noted that the internal consistencies of the Flight and Freezing subscales are potentially a little lower than ideal, however they are each comprised of only several items, and so this may be expected. The results of this cross validation show that both the classic BAS and revised BAS, and also the classic BIS and revised BIS scale, correlate to about. This obviously also makes clear that a large portion of the variance does not overlap 75% , and so as a consequence the Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q are clearly measuring something related to yet distinct from the Carver and White dimensions. The final aim of this study was to examine individual differences of the BIS in relation to a genetic variation on the AVPR1a gene. In line with the previous literature, we showed that the gene coding for vasopressin 1a receptor is involved in human anxiety. Carriers of the CC variant of rs11174811 showed significantly elevated anxiety scores, measured in terms of Gray's Behavioral Inhibition System. As already described above, expression levels in homozygous C-allele carriers genotype CC have been reported to be significantly lower compared to carriers of at least one minor A-allele genotypes AA or CA;. As a consequence, a putatively lower number of vasopressin 1a receptors are associated with elevated anxiety levels, because the anxiety lowering effects of vasopressin cannot unfold completely due to lower binding possibilities. But: This interpretation would be against the findings from genetic animal research showing that knocking out the AVPR1a gene is associated with lower anxiety. Interestingly, rs11174811 showed a significant effect on both the BIS measured with the Carver and White scale, as well as on the revised BIS measured with Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q. Given the correlation of 0. How can this be explained? When comparing Carver and White's BIS and Reuter and Montag's BIS scale it is apparent that Carver and White's BIS is a little more multifaceted compared to our revised BIS scale. More specifically, Carver and White included a wide range of BIS items in their questionnaire, ranging from explicitly feeling anxious e. In contrast, the revised BIS scale of our newly designed questionnaire includes no item explicitly referring to feeling anxious. Instead, Reuter and Montag's revised BIS scale describes being unable to bear uncertainty or often being indecisive, which targets one major issue in the revised RST. From our point of view, the overlap between the scales and the genetic effect targeting the shared variance could possibly be explained by the aspect of restlessness when being confronted with an unpleasant event in the Carver and White questionnaire , which is close to our concept of being indecisive or overly careful when confronted with uncertainty. Importantly, the genetic effect of rs11174811 was only significant in the context of BIS sensitivity; no significant effect was observed on the FFFS scale, measuring individual differences in fear and avoidance tendencies, nor any other RST scales on either of the questionnaires administered. The genetic variant investigated in this study seems to target anxiety, but not fear, in terms of the conceptualization of Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q. This finding supports the divergent validity of the BIS and FFFS dimensions in the rRST-Q, a key aim in the development of this questionnaire, and is potentially of wider importance for the revised model of RST, in terms of identifying neurobiological markers that reliably distinguish between trait measures of these constructs. Clearly, the genetic finding in this study represents a beginning point in this process, but an important beginning point nonetheless. It should be noted that there are existing attempts to develop self-report measures in the context of revised RST e. For example, suggested the original Carver and White BIS scale could be decomposed into separate BIS and FFFS dimensions, based on an evaluation of the item wording and results of confirmatory factor analysis. Thus, the genetic data reported in this study represents a relatively novel and important step in this endeavor. Conclusion Reuter and Montag's rRST-Q is a new self-report measure, developed in line with theoretical assumptions derived from Gray and McNaughton's RST. The psychometric properties of the scale, including its factorial structure and internal consistencies were supported in both a German and English language version of the measure. A first validation study using a molecular genetic approach found a significant association between a functional polymorphism on the AVPR1a gene rs11174811 and the BIS. Further, the genetic association was not shown for the FFFS dimension in the rRST-Q, supporting the divergent validity of the BIS and FFFS dimensions in this scale, and highlighting a potentially useful genetic marker that could be used to evaluate existing or new measures developed under the revised RST. This study should clearly be seen as a first step in the validation of this new revised RST measure. In particular, no validation of the revised BAS scale was attempted in this study, and this may be a focus for future work on this scale. More broadly, future studies will be needed to search for further genetic, endocrinological and brain imaging validation of this new inventory. In addition, this new tool will also need to be further evaluated in relation to other self-report measures and using theoretically relevant behavioral and experimental laboratory tasks. Conflict of Interest Statement The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The FFFS was already included in the original version of the RST as the so called FFS and was activated by unconditioned unpleasant stimuli. BIS correlates with Harm Avoidance and Neuroticism at about 0. These two genes code for the vasopressin 1a or 1b receptors. Of note, the gene coding for the 1b receptor has not been the major focus of research until now. References Keywords: reinforcement-sensitivity-theory, anxiety, fear, revised RST questionnaire, AVPR1a, rs11174811 Citation: Reuter M, Cooper AJ, Smillie LD, Markett S and Montag C 2015 A new measure for the revised reinforcement sensitivity theory: psychometric criteria and genetic validation. Reviewed by: , University of Munich, Germany , Sapienza University of Rome, Italy Copyright © 2015 Reuter, Cooper, Smillie, Markett and Montag. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the. The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author s or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

The difference between classical and operant conditioning - Peggy Andover

Social phobia: Overview of community surveys. Primenjena psihologija, 5, 335-356. Reinforcement sensitivity theory RST proposes three brain-behavioral systems that underlie individual differences in sensitivity to reward, punishment, and motivation. The Neuropsychology of A nxiety: An Enquiry into the Fun ctions of the Septo-Hippocampal Syst em. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 902- 906. Importantly, the genetic effect of rs11174811 was only significant in the context of BIS sensitivity; no significant effect was observed on the FFFS scale, measuring individual differences in fear and avoidance tendencies, nor any other RST scales on either of the questionnaires administered. Behavioural Brain Research, 225, 455- 463. We would expect only moderate correlations between the same constructs measured across the two self-report-inventories given the differences between the classic and revised models of RST, as outlined above. Consistent with this, studies have shown the inhibitory effects of pain and its positive correlations with negative cognitive processes and anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences. Judgment and Decision Making, 5, 411- 419. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.

[Zene za udaju sa sela|Crnka nudi ugodno druženje i masaže|Hot matorke srbija]

Post je objavljen 31.12.2018. u 08:31 sati.