Marketing

18.9 miliona KM vrijedno istrazivanje!! Probajte i sami

No, vikend je, za isti slijedi par laganijih testova/vjezbi, inace nesto sto je kod nas posljednjih desetljeca zaboravljeno, zato se naravno krivi rat, no rat je davno zavrsen, stoga slijedi malo vjezbanja :) Dio vjezbi je na engleskom:

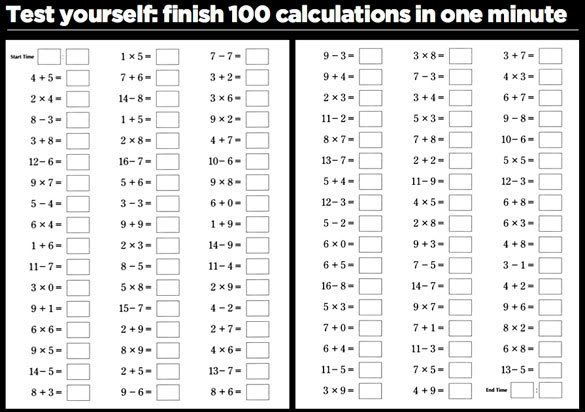

Probajte ovu prvu tabelu rijesiti u sto kracem vremenskom roku:

Koliko vam je trebalo? Jedna minuta ili jos manje? Onda zasluzujete zlatnu medalju. Ili jedna minuta i trideset sekundi? Ako ste sve rijesili izmedju minute i minute i po onda zasluzujete srebrnu medalju. Do dvije minute, nazalost samo bronza. No, ako vam je trebalo vise od dvije minute onda vjezbajte jos malo.

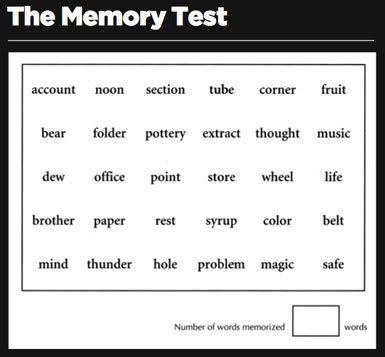

Gledajte u ove rijeci dvije minute i onda pokusajte da zapisete na papir sto vise rijeci mozete, u sljedece dvije minute.

Ostatak vjezbe je na zalost na engleskom jeziku, i ne zaboravite da je ovo istrazivanje kostalo 18.9 miliona KM:

Here's a question for you: what's 4 + 8? You can do that one? OK, then how about this: 2 x 4? Good. Now try these: 8 - 3? 3 + 8? 12 - 6? 9 x 7? Perhaps you had to think for a fraction longer about that last one, but I'm sure you got there (if you didn't then we could be in trouble).

These are easy questions, hardly a tough test of the old grey matter. If I told you that they were the key to a rigorous mental training regime that would boost your brain power you'd laugh in my face. But could you compute the answer to each of those questions and write it down in 0.6 seconds? And do 100 similar questions in one blistering rush? If you can, then you won't need telling that's 100 questions in one minute. If you really can do that you have either been manufactured in Silicon Valley or you have been doing some serious brain training.

Perhaps you have been following the programme devised by Professor Ryuta Kawashima, a Japanese neuroscientist. After all he claims to have spawned two million brain trainers worldwide. Now his bestselling brain health workbook is coming to Britain. I have just completed the 60-day course.

Kawashima, of Tohoku University, says that brain function naturally begins to deteriorate after the age of 20, but by providing daily stimulus for the brain, in the same way that the body requires exercise to maintain fitness, the deterioration can be stopped. He claims to have devised a series of exercises that increase delivery of oxygen, blood and amino acids to the prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain that makes up much of the frontal lobe, which is responsible for creativity, memory, communication and self control. The programme is designed for those suffering from forgetfulness, difficulty remembering names, how to spell words or express thoughts, or who wish to work on creativity, memory skills, communication and slowing the mental effects of ageing.

That would be all of us then. Personally, while I'd have been delighted to improve in all those areas, I was looking for a boost to my memory. The other day I heard a playwright on the radio complaining that he would go to the theatre and then when he was subsequently asked what he had thought of the production he would find that he could not remember. I sympathised fully with this. I can't remember who said it.

I have a handful of friends with near total recall. While they speak fluently, effortlessly summoning references and in total control of anecdotes, my end of the conversation is like playing 20 questions and punchy, potentially hilarious, stories are spoiled by my lack of command over the crucial details. I have always meant to send off for one of those courses you see advertised in newspapers under headlines like: "Do you forget names, faces, who you are?" But it always slips my mind to fill out the coupon. One day, when Google is plugged into our brains, this will not matter. But until then we must see if the likes of Kawashima can do anything for us.

Before starting the 60-day course, the Train Your Brainworkbook offers a Pretraining Prefrontal Cortex Evaluation, consisting of three short tests. The first is to count to 120 out loud as fast as possible, enunciating clearly. I did this in 42 seconds. The second test is much harder. You have two minutes to study a list of 30 words and then a further two minutes to list as many as you can remember. I scored 14.

The third test is called a stroop test; four colours – blue, green, red and yellow – are written out 50 times. The words are mostly printed in a different colour from the word they are describing. The trick is to recite out loud as fast as possible the colour in which each word is printed. It's tricky and took me 49 seconds. These tests are to be repeated every five days. On every intervening day you take the simple arithmetic test. All results are logged on graphs to enable progress to be monitored. By looking at pictures of the brain taken by a brain-imaging device during a range of activities Kawashima concluded that the most effective way of activating the brain is to solve simple calculations quickly: "Solving difficult calculations, surprisingly, does not activate much of your prefrontal cortex at all." Research that he conducted with students found that they could remember 20 per cent more words in a two-minute memory test after they had done the simple maths test. The sums acted as a warm-up for the brain. So it might just be worth running through a few sums before that important meeting when you want to impress the boss by listing all the key points without looking at your notes.

I worked my way through the first set of 100 calculations. I made steady progress. Looking at my workbook now my writing is very neat compared with later tests when I was scrawling the answers in an effort to finish faster. I took 3min 20sec and did not get any questions wrong. The next day I had reduced this to 2.46 and two days later to 2.15. Then in the second week I hit 1.58. Anything quicker than 2 minutes is classed as a bronze medal and according to Kawashima you are a "calculation master". He says most people will hit a wall, but it is "important to hang in there and continue your training, a breakthrough will come, and your scores will suddenly jump". This is true. Unfortunately, my scores jumped backwards. Sometimes I was as slow as 2.30. The trick to going faster, I gradually discovered, was to keep on a roll, like a sprinter who does not inhale properly.

Sometimes I stumbled over a question. In the heat of the moment it is surprising how you can have a crisis of confidence over 6 x 9 or 17 - 9.

Once that happens it is hard to recover a good flow. The answer is not to think too hard or worry about getting questions wrong but to trust to instinct. Kawashima says that it doesn't matter if you make mistakes. I often got one wrong answer, sometimes more, usually because I misread a question in haste. But the occasions I got three or four wrong answers was usually when I also made a slow time. By the third week I was regularly back in the bronze medal position and here I reached a plateau just below two minutes. It was not until the 45th day that I began to maintain a regular position tantalis-ingly close to the 1min 30sec mark and the silver medal.

Every five days I took the prefrontal cortex evaluations. I fairly quickly reduced the time it took me to count to 120 out loud to scores in the 30-seconds-plus range and hit 34 seconds on the last day. The tricky stroop test, involving reading the colours, saw me hovering around 30 seconds for the duration. I peaked at 28 seconds on the penultimate test and dropped back to 30 seconds at the end. The word memorisation was toughest. I tried to construct stories from the words and said them repeatedly out loud and underlined them as I fought to commit the words to memory. My graph of the number of words recalled zigzagged up and down, with my lowest score on the first day and my highest, of 21 words remembered out of 30, in the test at the end of Week 8. The rest of the time I scored between 15 and 20 words. It's hard to use the stats to make a case that I improved hugely over the duration of the course.

Back with the daily sums there was some improvement. On Day 55 I hit the magic silver medal position with a score of 1.29. Tragic though this might sound, I was mildly elated. A bit like the first time you finally swim a width of the swimming pool underwater. I hit 1.28, then 1.27 and then on the 60th and last day of the course, with a supreme effort and the extra motivation of knowing this was my last chance, I somehow blazed my way to 1.19. I was nowhere near the gold medal position awarded to those who can do all 100 questions in one minute and I can't imagine how this is humanly possible. Kawashima says that this is within the capability only of a "numbers whiz" who often calculates manually or regularly uses maths at work. I was happy enough with my achievement and the fact that for the first time in my life I could call myself a "calculation expert". I was genuinely rather astonished at the speed with which I could now complete the tests.

But does it mean anything more than that daily practise had enabled me to get faster at doing a certain type of simple maths test? Certainly, I have been giving my brain a little work out for a few minutes every day and if we accept that Kawashima's research is sound, then that could be helping to stave off the long-term mental effects of ageing. Hard to quantify, but for the sake of a few minutes a day, it might be worth a try. Then again, I might just stick to my routine of doing the chess puzzle set by my colleague Ray Keene.

Much harder to determine is whether I'm more creative or communicating better than I was 60 days ago. And as for my memory, well, even with my storytelling strategy I didn't score convincing improvements in the word memorisation test. I did surprise myself the other day by remembering the name of a hotel in the Atlas mountains that I stayed in five years ago. That's the sort of thing I would normally have had to Google and I remarked upon this to a colleague. "Yes," she said. "You told me that yesterday."

Post je objavljen 17.02.2007. u 19:40 sati.