pookapookapookapookapooka

utorak, 08.01.2008.

GOD DAMN

|

Whatever good man is able to do through his own efforts, under laws of freedom, in contrast to what he can do only with supernatural assistance, can be called nature, as distinguished from grace. Not that we understand by the former expression a physical property distinguished from freedom; we use it merely because we are at least acquainted with the laws of this capacity (laws of virtue), and because reason thus possesses a visible and comprehensible clue to it, considered as analogous to [physical] nature; on the other hand, we remain wholly in the dark as to when, what, or how much, grace will accomplish in us, and reason is left, on this score, as with the supernatural in general (to which morality, if regarded as holiness, belongs), without any knowledge of the laws according to which it might occur. |

| < | siječanj, 2008 | > | ||||

| P | U | S | Č | P | S | N |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

Dnevnik.hr

Gol.hr

Zadovoljna.hr

Novaplus.hr

NovaTV.hr

DomaTV.hr

Mojamini.tv

MOŽETE ZBUNJIVATI NEKE LJUDE CIJELO VRIJEME, MOŽETE ZBUNJIVATI SVE LJUDE NEKO VRIJEME, ALI MORATE ZBUNJIVATI SVE LJUDE CIJELO VRIJEME

nopasaranpooka@gmail.comCopyright by Microsoft Corporation

All rights reserved under condition of their actualisation only under the terms described in various fairytales as ''good'' or ''benevolent'' or ''motherfucking unconditionaly determined never to back off when confronted with forces labeled as 'enemy' by the power invested in pooka by the truth that we all hold as selfevident, one of which is unexceptable material wealth of Microsoft Corporation, hereby denied of the copyrights given above.

spot the loonie!

Immanuel KantImmanuel Kant & quantum mechanics

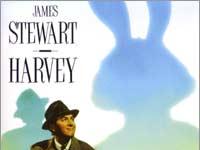

Harvey

JEFFERSON BIBLE

Jesus of Nazareth

Wes Clark

Karl R. Popper

Ludwig van Beethoven

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Fjodor Mihajlović Dostojevski

William Shakespeare

Joseph Heller

William Blake

John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Aleksander Shulgin

Jean Baudrillard

Leonard Bernstein

Paul Feyerabend

Leonard Cohen

Hundertwasser

Kurt Vonnegut

Slavoj Žižek

dr. Albert Hofmann

Douglas Adams

Erwin Schroedinger

Rabinranath Tagore

Jello Biafra

Charles Darwin

John Maynard Keynes

Hieronymus Bosch

dr. Leo H. Sternbach

Harry Truman

GEORGE MONBIOT reanimated pooka orIMOGEN

alje soft cell porto tofu walking eviltwin plavi golub korvin natch sonic medusa celeste nymphea neurotic palagruza mantasmic DUCE DUECENTO poni

Link o razlozima zašto Danijel treba našu pomoć da bi mogao živjeti Broj Danijelovog računa je: Danijel Subanović, Zagrebačka banka, Zagreb. Kod plaćanja e-zabom u račun primatelja treba upisati slijedeće: 2360000 - 3112916704. Poziv na broj ostaje prazan. Za plaćanje u pošti, banci ili Fini, Nalog za plaćanje (opća uplatnica) treba ispuniti na sljedeći način: Primatelj: Danijel Subanović, Model: 14, Broj računa primatelja: 2360000-1000000013 Poziv na broj: 3112916704