09

utorak

travanj

2013

Why voter turnout will be low in the forthcoming European Parliament Elections in Croatia?

“Where few take part in decisions there is little democracy”, declared Sidney Verba and Norman Nie in the book on “Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality”. Widely present stagnation of voter turnout is triggered by large-scale political apathy, arousing from disillusionment and disaffection with the formal political process. This, in turn, causes a crisis of legitimacy of representative democracy and endangers participatory society.

How to make the 28th European star shine?

I expect same trend will be confirmed in the forthcoming elections for the European Parliament (EP) scheduled for 14 April 2013. Croatia's accession to the European Union is scheduled for July 1 2013 and until regular EP elections in spring 2014 the 12 members of the EP elected by the Croatian citizens will hold their seats. Croatia currently has 12 observers in the European Parliament, who were appointed by the Croatian Parliament in March 2012, according to the representativeness of political parties in the national parliament.

After the Croatian President Ivo Josipović announced on 1 March 2013 the decision on the date of the EP elections, opposition parties and NGO activists complained that there would not be enough time to explain the importance of the election which would probably result in a low turnout. The Prime Minister Zoran Milanović argued that six weeks before the elections for the EP was enough time to motivate citizens and convince them of the importance to go to the polls, saying however he was aware that the turnout would probably be lower than at usual parliamentary elections.

BalkanInsight informs that analysts have expressed concerns that a low turnout could overshadow the election, with predictions suggesting that even a 30 per cent turnout could be counted as a success.

In the occassion of his visit to the City of Vukovar on 8 April 2013, the Vice President of the European Parliament, Mr Miguel Angel Martinez invited the Croatian citizens to cast their votes for the EU. He argued that the EP elections turnout is very important, recalling that in the last EP election the turnout in some member countries was a mere 20 per cent and that their deputies were always being asked who they represented and were not always taken seriously.

Why the EP elections are not the festival of democracy?

An insight into data on political participation at the pan-European elections indicate that this elections are not able to mobilize a significant electorate. Since the first European elections held in 1979, voter turnout has been falling in the occasion of each consecutive elections. Back in 2009, a large-scale, Europe-wide post-election survey was conducted in order to explore the reasons for abstention in the EP elections held between 4 and 7 June of 2009. The results of the study highlighted that there are significant differences between Member States or groups of Member States, in socio-demographic terms, but also in the light of a number of other variables concerning respondents' attitudes on polling day (voters and abstainers), and their opinion of the EU.

For example, turnout was particularly high in 3 countries: Luxembourg (90.76%) and Belgium (90.39%) where voting is compulsory, and failure to vote may result in a fine, as well as in Malta (78.79%). Turnout was higher than the European average in 11 countries: Italy, Denmark, Cyprus, Ireland, Latvia, Greece, Austria, Sweden, Spain, Estonia and Germany, with a rate which varied from 43.27% in Germany to 65.05% in Italy. Turnout was below the European average of 43% in 7 countries: France, Finland, Bulgaria, Portugal, the Netherlands, Hungary and the United Kingdom; where participation varied from 40.63% (France) to 34.7% (the United Kingdom). Finally, turnout was below 30% in the group of those 6 countries: Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Romania, Poland, Lithuania and Slovakia, where less than a fifth of the electorate voted (19.64%). All the Member States in this last group, in which turnout was well below the European average, are countries in Central or Eastern Europe

The survey, for example, established that a marked difference in turnout between new Member States (i.e. those that joined the Union in 2004 and 2007, respectively) and old Member States is a result of a stronger tendency to abstain from elections of any kind in new Member States. For example, 26% of interviewees in new Member States are considered to be 'regular voters', whereas 'regular voters' account for 43% of respondents in the old Member States. Similarly, regular abstainers represent a far higher proportion in the new Member States (33%) than in the 15 old Member States (19%).

It seems the EP is an institution the EU citzens perceive as distant and not legitimate. Namely, when the turnout in national and European elections were compared in the two consecutive voting cycles, it turns that turnout is regularly higher in national than in the EP elections in all Member States. E.g. there are 33% of Europeans who voted in the last national elections but opted to abstain in the European elections. In spite of the fact that the difference between the national and the European elections has reduced noticeably in the observing period, country by country evolution of turnout does not seem to follow any general trend across all countries. Consequently, no general trends can be identified, since situations vary from one country to another.

European Parliament Elections: Stunning Example of Losing Trust in Institution

Citizens support for the political system in which they live is important, since only those political institutions that are supported and trusted by citizens can act and function democratically. It is therefore striking that almost a third of abstainers in the latest European Parliament elections (28%) claim they did not vote because of lack of trust or dissatisfaction with politics (particularly important explanation for respondents in Greece (51%), Bulgaria (45%), Cyprus and Romania (both 44%)); in second place, quite a long way behind, they argue they lack interest in politics (17%) (significant for respondents in Hungary and Malta (both 29%) and in Spain (26%)); and claim to believe that voting does not change anything (also 17% of respondents who abstained voting, but strongly presented among those in Latvia (38%), Austria (35%) and Bulgaria (31%)).

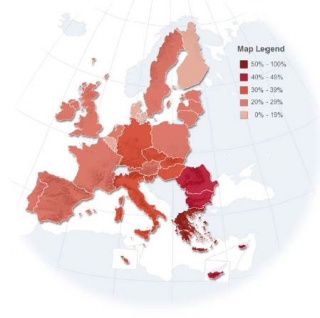

When respondents who did not vote (57% of the total sample) were asked to enlist the main reason which made them abstain, 28% of non-voters enlisted lack of trust and dissatisfaction with politics in general as their motives. The map below illustrates in which Member States lack of trust and dissatisfaction with politics in general is most often cited as reasons for non-involvement in the political process at the pan-European level. Indicatively, the ratio of respondents who justify their abstention through those arguments is higher in new Member States (of Central and Eastern Europe) as well as in the South-Eastern Europe old Member States (Italy, Greece). Such a divergence, again, can serve as an argument that political culture varies across the EU.

The abstention in the European elections reflects a general lack of interest in, or even a degree of distrust in politics. The above pictured analysis of how close respondents feel to the political parties confirms their gradual distancing from politics: fewer than half of respondents said they felt close to a party (43%, compared with 54% said they were 'not really close' or 'not close at all'). Comparison between Member States shown in the graph indicates that attachment to political parties seems weaker in CEE countries. In Hungary, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Poland and Romania, support for a political party is less common than in the EU as a whole, where such support is shared by 43% of respondents.

The Eurobarometer analysis also surveyed Europeans who voted in the latest European elections, 43% of the total sample. By interviewing them, the research attempted to establish why those who turn into voting stations decided to vote and, in particular, which of the themes determined their choice. The voting pattern remained relatively stable in the last two elections of 2004 and 2009. Half of the voters remained loyal to their political ideological option.

In order to explain this consistency of voting patterns, Jack Citrin’s argument can be recalled. Namely, in an article titled “The Political Relevance of Trust in Government” he claims that “performance of political officeholders and institutions determines their legitimacy. To be sure, an individual’s ideological orientation and policy preferences influence his evaluations of governmental behaviours, but such mediating effects are quite consistent with a theoretical emphasis on political events and experiences as the main source of public support for the political system.” Around one third of the voters (34%) chose their candidate some considerable time in advance (a few weeks or months before the day).

Even among European citizens who are politically active, a North-South divide over the timing of the choice can be traced. For example, Jack Citrin noted that “[r]espondents in the Southern [Member] States are more likely to make their choice in advance – whether because they always vote the same way, or because they make their decision a few weeks or even months in advance - while voters in northern countries are less decided, and seem to hesitate until the last minute. Respondents in Greece (13%), Malta (12%), Cyprus and Spain (both 11%), Portugal (8%) and Italy (6%), are all less likely than the European average (15%) to have taken their decision in the last days before the election or even on the day itself; conversely, a quarter or more of respondents in Latvia, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark and Finland took their decision in the final days or on election day.”

komentiraj (0) * ispiši * #